Three Lies and then Some

27 December 2017

We also visited Paul Revere’s house. Paul Revere is well known for riding north in April 1775 to warn of a plan of British troops to head that way, and that local revolutionaries, Samuel Adams and John Hancock, were to be arrested. The latter part wasn’t true and Revere wasn’t the only rider who raised the alarm but he was later celebrated in a poem that became famous and thus he for his heroic feat. Paul Revere later became wealthy due to his skill as a silversmith, and from what I saw today, it was indeed beautiful. What held my attention though was that he had 16 children, half with one wife and half with another. Some of the children died young but I couldn’t imagine even half of them living in the house we saw today. Although Paul Revere’s house was originally two storeys and about the size of the house viewed today, in the time Revere lived there, it had a third storey. When the house was obtained for preservation purposes in the early 1900s, the expert architect declared the third storey wasn’t there in Revere’s time so had it removed. Since then, the timber has been dated properly and declared that it would have been. Oops!

|

| The view of Charles River and over to Cambridge from where we have breakfast at our hotel in Boston (Back Bay) |

It is so frickin’ cold in Boston, rather than attempting a self-guided walking tour of the Freedom Trail, we booked a private car tour instead. Such a good decision. Even the local news is providing warnings of hyperthermia and record lows. Tomorrow or the next day they are predicting below zero figures. That’s below zero Fahrenheit!

Originally we were going to do Boston one day and Harvard the next but with a car and expert driver at our disposal we knocked over both in two days. It helped that we were reluctant to leave the vehicle to cover anything on foot.

Our driver, Derek, was cheerful and informative, busting the myths of history and legends. Boston is full of them. At Harvard, the statue on Harvard Yard to honour John Harvard is nicknamed the statue of three lies. The inscription claims that Harvard University was founded in 1638 by John Harvard, the man in the statue. The three lies are:

- There is no existing image of John Harvard so the statue was modelled on some random person. Well, not completely random, someone distinguished who later became a member of Congress.

- John Harvard did not actually found the university but was the first major benefactor to the university through a donation that included 400 books.

- The university was founded two years earlier, in 1636 as New College, receiving the name Harvard University in 1639.

The centre layout of Harvard was described as a four leaf clover by Derek, with three leaves being the shops, bars and other auxiliary matters, with the remaining leaf the actual school. Harvard stretches way beyond this hub though. The residences and offices go for miles and various schools are not even in Cambridge. For example, the medical and business schools are located separately across the Charles River, the medical school being within walking distance of our hotel.

|

| George Washington's house when he attended Harvard Univeristy after scorning the four bedroom house he was originally allocated |

We then started our Freedom Trail journey at the Battle of Bunker Hill Monument. Only the monument wasn’t at Bunker Hill. In fact, the battle was not at Bunker Hill either. According to Derek, the battle was meant to be at Bunker Hill but the crew sent to fortify Bunker Hill the night before the British arrived were drunk or lazy or both and stopped at a significantly flatter place, Breed’s Hill. The Americans lost this battle in terms of land and position but caused serious damage to the British troops, including killing around 200 of their officers through guerilla warfare. Hence, it could be argued, if they had gone on to the intended location, the American Revolutionary War could have been done and dusted then and there in June 1775.

|

| Bunker Hill Monument (on Breed's Hill) |

We also visited Paul Revere’s house. Paul Revere is well known for riding north in April 1775 to warn of a plan of British troops to head that way, and that local revolutionaries, Samuel Adams and John Hancock, were to be arrested. The latter part wasn’t true and Revere wasn’t the only rider who raised the alarm but he was later celebrated in a poem that became famous and thus he for his heroic feat. Paul Revere later became wealthy due to his skill as a silversmith, and from what I saw today, it was indeed beautiful. What held my attention though was that he had 16 children, half with one wife and half with another. Some of the children died young but I couldn’t imagine even half of them living in the house we saw today. Although Paul Revere’s house was originally two storeys and about the size of the house viewed today, in the time Revere lived there, it had a third storey. When the house was obtained for preservation purposes in the early 1900s, the expert architect declared the third storey wasn’t there in Revere’s time so had it removed. Since then, the timber has been dated properly and declared that it would have been. Oops!

In the lead-up to the revolution it took quite the campaign by the Sons of Liberty to garner support from the general public. [Editor’s note: 2015 mini-series of Sons of Liberty could be interesting]. The Boston Tea Party in 1773 is famous worldwide and was a great symbolic act performed by the Sons of Liberty that helped to escalate matters. However, one of the more important turning points in gaining public support earlier on was the propaganda surrounding what is referred to as the Boston Massacre in 1770. This was described to us as something that started as some boys picking on a British sentry with throwing snowballs, possibly with chunks of ice or stones within them. The sentry called for support and a dozen or so soldiers arrived. The boys called for support and approximately 200 people arrived. There was quite a verbal commotion until one of the locals struck a soldier to the ground and the soldier’s gun fired accidentally in the fall. This prompted the other soldiers to fire freely at the crowd. Some died immediately, others took longer. All up, five died. The British reported it fairly accurately as a riot. The Sons of Liberty were heavily involved in the printing industry and issued proclamations of it being a massacre, which the town crier duly called out in his announcement of Boston’s news.

Throughout the tour I was pegging these dates against Captain’s Cook 1770 visit to Botany Bay and Arthur Phillip’s arrival at Sydney Cove with a bunch of convicts in 1778. With all the other history lessons we have learned on this trip, it makes more sense of the convict settlement in Australia (America no longer taking them) and the lack of support Australia received (conflict occurring on many fronts).

So there you have it, a bunch of alternative facts and fake news. Nothing much has changed in 250 years.

|

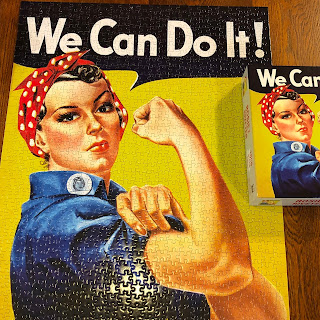

| Just because we could. Well, John anyway. The rest of us stayed in the car. |

Comments