The Drover's Wife - Review

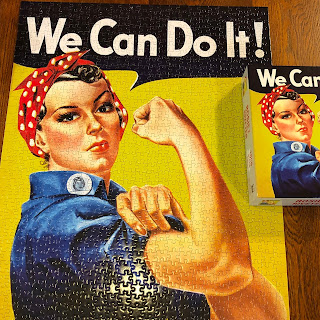

Photo: Stu Rapley, https://flic.kr/p/8SfTsV, CC BY-ND

The short story of The Drover’s Wife by Henry Lawson was a favourite of mine as a child, my mother often reading it aloud upon request. Its depiction of a woman facing isolated rural existence with four young ones and an absent husband added to my eternal fear of snakes and tapped into my loneliness. It introduced me to new phrases with my young mind puzzling over “castles in the air” for so long it now feels etched into my brain. I worshipped the strong and stoic woman, and her dog, Alligator, his name conjuring up a graphic image of a gnarly beast.

Leah Purcell has taken this story as inspiration for her own version of a drover’s wife. In Henry Lawson’s tale a handful of dramatic events were reminisced over during the night of waiting for the snake to appear. Due to the sameness of the land and its days, these occasions were rare, perhaps years apart. Well, they were all jam-packed into the Belvoir Theatre in the hour and a half experience, the busiest three days a drover’s wife has ever seen. There were numerous visitors (partially based on characters from the original drover’s wife’s reminiscences), the coming and going of her son (Danny), a birth, and a few deaths. This frenetic activity was necessary to cover the multiple feminist and indigenous issues addressed by the play but detracted from the plausibility of the story.

The feminist issues were most confronting in their physicality. There was audience laughter at labour pains as the drover’s wife swung her gun around at unwanted visitors, weaker laughter as her waters break, and a mixture of laughter and horror at the declaration that one foot had already popped out. Later her breast milk leaks down the front of her clothes and is visible for the remaining time. As the play reached its climax, there was a rape scene where the perpetrator took time reaching his. An audience member walked out.

The drover’s wife has a name in this version, Molly. No other women were seen on stage but they were talked about. Two white women performed treachery upon Molly but black female characters were represented with more affection.

A raft of indigenous issues were covered, starting with a wrongful arrest, featuring an iron collar digging into the prisoner’s neck, and concluding with taking the children away. Likewise, Molly started trapped in the mentality that all Aboriginal people are trouble, her opening sentence ending with “you black bastard” but ended with all her prejudices taken away, embracing the culture. Since this radical transformation occurred over a mere three days it was difficult to believe, despite all the drama that had entailed over this time.

The set was simple and stark and thus worked well. A hessian curtain hung parallel to the back wall, acting as the hut wall and protecting the audience from witnessing the birth, a chopping stump and axe was placed centre stage, a substantial branch laid on the ground on one side and a gun was constantly on hand. Sand covered the floor depicting the action upon it until Molly swept it away.

The acting was superb. Despite just two actors playing the five white adult male roles, they were each distinct, yet equally reviled. Leah Purcell, on stage the entire time, embodied the character she wrote with passion and depth. This drover’s wife aligned quite comfortably with the strong and robust woman I had pictured decades ago. I attended on a Sunday evening, and even though I had issues with the pacing of the action, it provided a powerful punch to end an otherwise slow weekend.

Comments